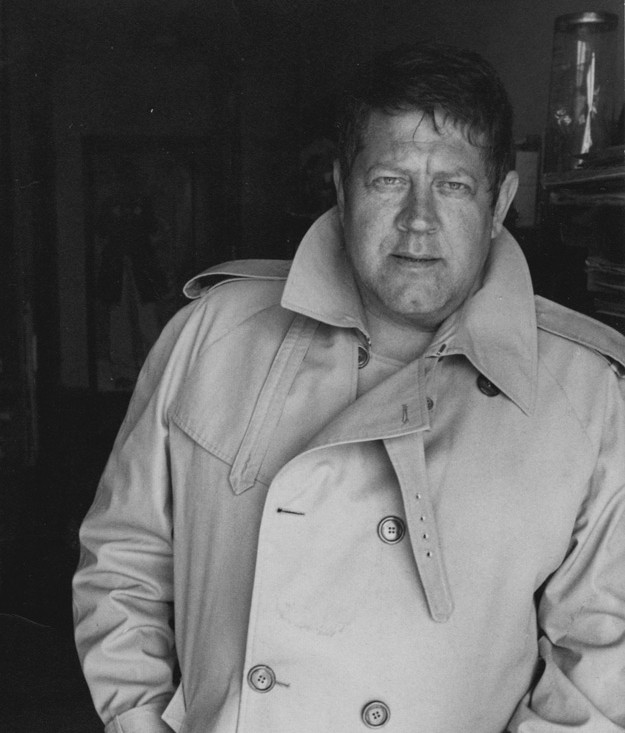

Hugo Pratt

Hugo Pratt is a novelist who illustrated his stories while dreaming of telling it all simply by drawing a line, and who, through his characters, explored the vast universe of the physical and mental voyage.

With bold blacks or pale watercolors, he transformed Corto Maltese, Banshee, Koinsky, or Shanghai Lil into everyone’s desires, each of us setting out towards a different treasure island and a world that is a bit freer of schemes and limits, a place where it is really worthwhile to live and possibly fulfill one’s dreams

Let’s attempt to construct a sort of biography of this Venetian, citizen of the world, he was born in Rimini in 1927.

His origins are already an interesting premise for all he will turn out to be. One grandfather, who grew up in Venice, was of English and French ancestry; one of his grandmothers was from Turkey. The other grandfather? A Sephardic Jew who had emigrated from Spain and was renowned both as a poet and podiatrist in Venice–a special kind of fellow. From this grandfather, the foot doctor and poet, Pratt inherited a great gift: his love of poetry.

“In literature what moves me the most is poetry because poetry is concise and unfolds through imagery. When I read, I see the images, I perceive them at skin level. Behind poetry there is a hidden deepness that I can sense immediately and, as with poetry, the cartoon strip is a world of images, one is forced to conjugate two codes and consequently, two worlds. An immediate universe through imagery and a world mediated through words.”

A Conversation with Hugo Pratt, Tandem , December 1989

In this special family the grandmother held an important role. She would take Hugo to the movie theater to see adventure films and, once they were back home again, she would tell him, “Hugo, now draw what you saw.” Then as a reward there would be hot chocolate with cookies in the company of her lady friends and his aunts: another universe, heterogenous and female.

His mother Evelina loved cards, especially the Tarot cards, with which she would read the future of her women friends and clients, who were so numerous that this became a kind of work.

However, there were not just cards and movies in Hugo’s upbringing; there was the opera, too. When he was seven, his actress aunt took him to the Fenice to hear and see Wagner’s “Ring of the Nibelung,” thereby opening up the world of Germanic gods to him, while at the same time telling him about Jewish myths and the Cabala.

Tarot and other cards, the movies and the opera, gatherings of women, the fantastic and mythological world, the fluid and changing world of Venice–are all present in Hugo Pratt’s work.

Imagine what would happen if that same little boy were sent at age 10 to Africa, where his father is an officer in the Italian colonial army in Abyssinia, modern-day Ethiopia.

Back in Venice, the war now over, what could happen to Hugo Pratt the boy, in love with drawing and with a life experience full of images and stories to tell?

What else but establish, with a group of friends, a magazine which reveals their passion for the great American comic book artists, first of all Milton Caniff? Thus Asso di Picche (Ace of Spades) is born, named after the elusive avenger in the yellow stocking suit. Now, besides writing stories, living on the roofs of Venice, drawing, laughing, drinking, and playing music with friends to the rhythm of the new postwar sounds coming out of America, what more could a guy like him want?

Right, travel.

No problem. At age 22, together with his friends of the “Gruppo di Venezia” (Venice Group), Pratt departs for Argentina.

It’s a time of parties, of asado on the grill by the swimming pool, rugby, Tango, billiards; of youthful love and the birth of his children Lucas and Marina; but above all it is the time of his professional acquaintance with Hector Oesterheld, a socially committed writer and a great Argentinian screenwriter. These are the years of “Sgt. Kirk,” the renegade who makes friends with the Indians; of “Ernie Pike”, the war reporter; and of “Ticonderoga,” the wonderful story about the American Indians.

At this point, the young man from Venice–who ever since he was a boy had been drawing Indians and playing near his home in Campo San Giovanni e Paolo, shooting arrows at friends dressed up as cowboys–writes his very own story and calls it “Wheeling.” It’s a poem about the world of the North American frontier. He slips into the story too: in some of the strips, the face of the renegade Simon Girty is his, just to emphasize once more his love for the world and stories of the Indians.

In this period there is jazz, his friendship with Dizzy Gillespie, and his acquaintance with great South American literature, from Borges to Lugones, Arlt, and Dos Passos (whom he met on one of his trips to Brazil); and there are other trips: to Patagonia, Chile, the Caribbean, and Guatemala.

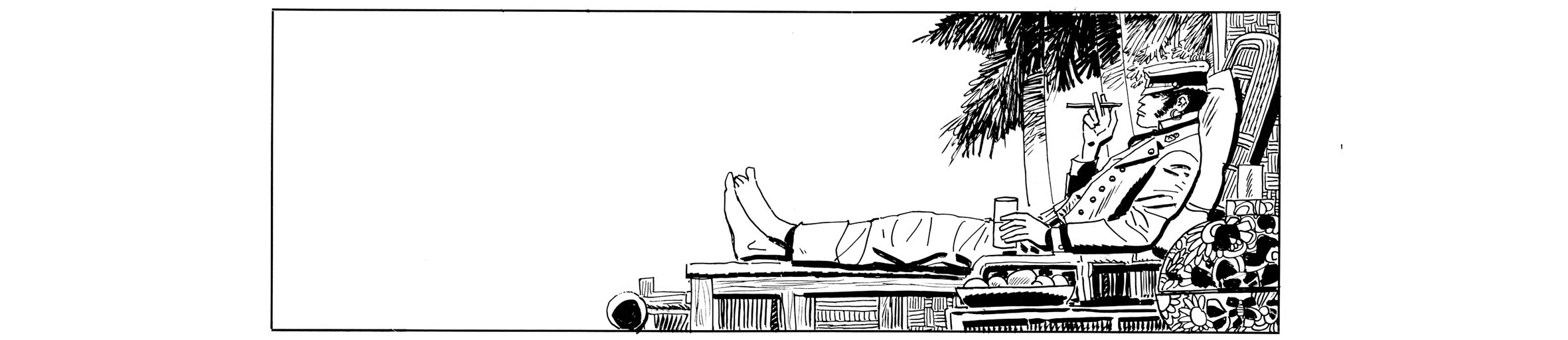

When an illustrator like Hugo Pratt, who has lived a life right out of the movies (as you have seen), with the experiences he had accumulated, is allowed at age 40 to draw whatever he wants, without worrying about contracts, without publishing schemes or strategies–well, when this happens, a masterpiece is born. It is “Una ballata del mare salato” (The Ballad of the Salty Sea), the first comic in comic strip history to earn the definition of “drawn literature,” and the sailor becomes a cult character not just for those who love oceans, palms, and pirates, but above all for those who love freedom.

With Corto now comes fame and the move to Paris. With the comic magazine PIF, which sells millions of copies, Corto becomes a serial hero; the stories of Corto Maltese over 25 years expand to 29, taking the sailor to practically every corner of the world: on the high seas, in deserts, steppes, and jungles. Nor is his creator far behind: Pratt travels from Africa to Canada, from Apia (Samoa) to Easter Island, just to mention the main cardinal points.

These years are not just about Corto. There are also The Scorpions of the Desert and Jesuit Joe, just to continue talking about south and north. There is also St. Exupery, who flies the skies one last time; and Mü, the last of the Corto stories, in which the fantastical universe of Hugo Pratt flies toward the magnificent nowhere of a vanished continent, much like its creator, who in 1995 passes away in Switzerland, where he had elected to live since 1984.

Marco Steiner